Search ARMI Database

Search term(s)

Contribution Number

Search Results

180 record(s) found.

Data Release Chorus Frog (Pseudacris maculata) survey data Cameron Pass Colorado 1986-2025.

News & Stories Amphibian Week 2025 a cross-country success!

Amphibian Week 2025 was celebrated by ARMI scientists who planned and participated in public events from Wisconsin to Florida and from California to Washington, D.C. Over 3000 people participated in these in person events.

On the west coast, amphibian events began early, in February and March, to get folks primed for Amphibian Week. Scientists from USGS Forest and Rangeland Science Center (FRESC, Oregon) partnered with US Fish and Wildlife Service Willamette Valley Refuge Complex to host information tables on two occasions during Winter Wildlife Field Days. ARMI scientists from Western Ecological Science Center (WERC, Point Reyes Field Station) joined FRESC in providing amphibian walks during Amphibian Week. The walk at Point Reyes engaged 4th and 5th graders in not only a walk, but a beta test of an amphibian game. The game was developed by the Einstein Fellows Program with input from ARMI scientists. In southern California (WERC San Diego Field Station) partnered with the Santa Ana Zoo to host a table with activities from coloring sheets to opportunities to practice monitoring for disease by collecting “DNA” on a cotton swab from a plushie “frog”.

In the Rocky Mountains (Fort Collins Science Center), an amphibian-themed art show, “Art Meets Science: The World of Amphibians” was held at a local venue showcasing local art from pottery to watercolors to frog-themed crafts. An evening amphibian walk drew a crowd. At Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center (Missoula Field Station), partners at the Washington Middle School presented a weeklong focus on amphibians with book suggestions and activities that melded biological science and library science.

In the Midwest, scientists from the Upper Midwest Science Center (La Crosse, WI) partnered with The Nature Place to present a talk and an evening amphibian walk. The activity at Myrick Marsh featured field gear like parabolic microphones to listen to frog calls. The National Wildlife Health Center (Madison, WI) partnered with the Kettle Moraine State Forest and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources to host drop-in Amphibian Week activities at the Southern Unit Headquarters in Eagle, WI.

On the east coast, scientists from the Wetlands and Aquatic Research Center (Gainesville, FL) hosted amphibian walks and talks in partnership with the Florida Museum of Natural History. In partnership with the Santa Fe College Teaching Zoo, ARMI scientists hosted an Amphibian Week event with talks, activity tables, and conservation games. The South Atlantic Water Science Center and the New Jersey Water Science Center showed an Amphibian Week informational slide show in the Center lobbies.

In Washington, DC, four ARMI scientists participated in an Amphibian Week kick-off event at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History’s Q?rious exhibit. This event included other federal agencies such as the US Forest Service, with ARMI scientists providing information, activities, games, and displaying live amphibians local to the east coast. ARMI also led an Amphibian Week event at the Smithsonian National Zoo at the historic Reptile House (which also houses amphibians), where scientists partnered with National Zoo staff to provide amphibian demonstrations, pose trivia questions, and provide information about amphibians. Phil the Frog was present at both events, dancing through life and providing inspiration to visitors and staff.

ARMI / USGS also participated in social media focused on Amphibian Week from official USGS posts on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn and X, to collaborating with partners such as NW Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation in developing posts for the week.

Papers & Reports Evolution of research on global amphibian declines

Papers & Reports Comments on: “Rewilding a vanishing taxon–Restoring aquatic ecosystems using amphibians”. Stark and Schwarz 2024. Biological Conservation 292, 110559

Papers & Reports Unburned habitat essential for amphibian breeding persistence following wildfire.

News & Stories ARMI scientists are delegates to the World Congress of Herpetology

The 10th World Congress of Herpetology was held in the city of Kuching, in Sarawak, Malaysia (northwest Borneo) August 5 – 9. ARMI scientists Brian Halstead, Blake Hossack, Pat Kleeman, and Erin Muths presented research papers. There were over 1400 delegates at the Congress, with > 900 contributed talks and 33 symposia.

Halstead and Muths organized a symposium targeted at graduate students (What Editors Want: A Guide to the Publication Process for Graduate Students) that included talks from 7 past and present editors, including Judit Voros, co-editor of Amphibia-Reptilia and Secretary General of the World Congress.

Hossack presented a talk co-authored by ARMI scientists Kelly Smalling and Brian Tornabene titled: “Energy-related secondary salinization of wetlands: Coordinated experiments and field surveys to identify mechanistic links with amphibian abundance”. This invited talk was included in the symposium titled: Haunting the seaside: Integrative biology of salt tolerance in amphibians.

Halstead presented a talk titled: “Effects of translocation and head-starting on giant gartersnake (Thamnophis gigas) behavior and survival”, co-authored by USGS scientist A. M. Nguyen and B. D. Todd (University of California, Davis). This invited talk was included in the symposium titled: Improving conservation and mitigation outcomes of snake translocations—global lessons.

Kleeman presented a contributed talk co-authored by Halstead and J.P. Rose (ARMI scientists), and collaborators from the Nevada Department of Wildlife, K. Guadalupe and M. West, titled: Initial demographic estimates for two species of narrowly endemic toads in central Nevada: Anaxyrus monfontanus and Anaxyrus nevadensis.

Muths’ presentation, co-authored by L. Bailey, A. Fueka, L. Roberts (Colorado State University) and B. Hardy (Chapman College), was in the symposium titled: Improving animal welfare. This invited talk was titled, “Methods in marking toads: PIT tagging versus photography”.

The World Congress is held every four years on different continents with the specific aim of facilitating attendance from herpetologists around the world especially those from developing countries. The first World Congress was held in Canterbury, Great Britain in 1989, with subsequent congresses in locations including China, Brazil, Australia, and Canada. ARMI hosted a symposium on amphibian decline in 2012 at the 7th World Congress in Vancouver.

Congress delegates in Kuching enjoyed multiple plenary talks with topics ranging from Bornean flora and fauna, to the Biogeography and Evolution of reptiles in the Arabian Peninsula, to Frog diversification in Old World tree frogs.

Papers & Reports Hosts, pathogens, & hot ponds: Thermal mean and variability contribute to spatial patterns of chytrid infection

Papers & Reports Of toads and tolerance: Quantifying intraspecific variation in host resistance and tolerance to a lethal pathogen

Data Release Amphibian (chorus frog, wood frog, tiger salamander) surveys in Rocky Mountain National Park (1986-2022)

Data Release Mercury concentrations in amphibian tissues across the United States, 2016-2021

Papers & Reports Terrestrial Movement Patterns of the Common Toad (Bufo bufo) in Central Spain Reveal Habitat of Conservation Importance

Papers & Reports Amphibians in a protected landscape: A 30 year assessment

News & Stories It's Always Halloween When You Work on Toads

As first appeared in USGS NTK:

My late fall trek to Lost Lake in Rocky Mountain National Park to look for evidence of toad breeding is beautiful. The aspen leaves are golden. The air is downright cold at the 7 am start. The ten-mile hike starts downhill but soon angles up and continues up for the next eight miles. That is a lot of time to think about the end of another summer field season and about how few toads we observed. I can’t help but wonder if our field techs somehow overlooked breeding and egg masses? Or was it because it didn’t happen? It was only early October, but I settled in to a decidedly grim and early Halloween-edgy mood that was resistant to the bright blue of the sky and clung to me like a veil the rest of the hike.

Not a soul was camping at Lost Lake. The lake was still with only a few ravens providing their opinions on campers and, no doubt, toad conservation. All senses narrowed to look for a toadlet or an adult toad as I poked through the drying grasses and shrubs around the lake, and hopefully scanned the water’s edge. I could feel, more than see, the daylight dwindling.

On the far side of the lake I saw her, sitting on the shoreline. I stopped short as I saw the stiffness of her body and the blank white stare of her eye. The toad was dead. But hadn’t been dead long. I pulled out the “tools of the trade” and measured her, checked her for an identifying passive integrated transponder tag, and swabbed her to test for the amphibian chytrid fungus. She was not marked, and I only assumed she was a female based on size. I recorded a few bits of environmental data, and although firm-ish, the toad was in no condition to travel for further examination. I felt a chill and realized that the sun was completely gone. I left her on the shore with a quick prayer to the amphibian goddess and a furtive look around for moose.

Boreal toads, like the one I found, have been on the decline in Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP), and the southern Rocky Mountain region for a while. One contributor to these declines is the amphibian chytrid fungus that thickens the skin, blocks osmosis (water intake), and eventually leads to heart attack and death. As a research zoologist, my colleagues and I have been working on amphibians in RMNP in northern Colorado for three decades. Our work ranges from questions of immediate interest to the National Park Service, like “how are the wood frogs doing with the hydrological changes on the west side of the park,” or “why are boreal toads declining” to overall management questions like, “what is the status of the amphibian species in the park and what factors may affect persistence?”

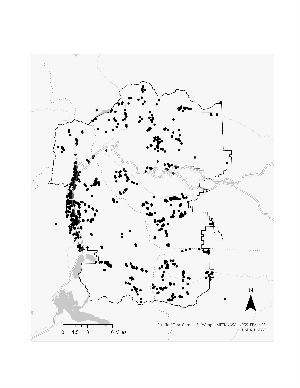

Although there are some bad days like my autumn hike to Lost Lake, there are glimmers of hope, or at least of gains in information that we might use towards amphibian conservation. We are currently working on a paper using three decades of data on chorus frogs, salamanders, and wood frogs in RMNP to examine changes in persistence over time across the landscape of the park. This work also considers a variety of mechanisms (e.g., visitor use) that may affect the probability of persistence and thus provides RMNP with information that can contribute to conservation decisions about the management of the park’s amphibians.

Erin Muths is a research zoologist at the Fort Collins Science Center and is a principle investigator for the Amphibian Research and Monitoring Initiative for the Ecosystems Mission Area. Her lab has studied boreal toads and other amphibians in the Rocky Mountains for more than 25 years. She is going to be sorcerer for Halloween.

News & Stories Do Your Halloween Plans Involve Eye of Newt? Newts Have Some Things They Want You to Know!

As first appeared in USGS NTK:

First of all, newts are not the villains, instead, they are often the victims.

Newts are at risk, along with many animals, from climate change and from disease. In fact, they could be poster animals for climate change: In southern California, recent record warm air temperatures along with peak drought conditions are linked with a 20% reduction in mean body condition (e.g., mass) in the California newt (Taricha torosa)*. The disease Batrachochytrium salamadrivorans (Bsal, literally eater of salamanders in Latin) has caused significant devastation to salamander populations in Europe. This fungal disease affects primarily newts and salamanders and the Northeastern U.S. is considered the salamander capital of the world. While Bsal is not present in the United States now**, there is serious potential for the disease to spread from Europe to the U.S. through the pet trade***.

Second, newts are quiet neighbors that contribute to society.

For example, newts eat a variety of insects, and they are eaten by birds, snakes, and some mammals.

Third, newts appreciate Halloween and keep it alive all year!

Newts have three distinct developmental life stages that are in effect, costume changes! They begin as aquatic larva, metamorphose into terrestrial juveniles (sometimes called efts), then metamorphose into adults.

And finally, newts value their eyes.

If you are really looking for some eye of newt, go look in your local grocery, “eye of newt” is actually a very un-scary and easily acquired mustard seed.

Erin Muths is a research zoologist at the Fort Collins Science Center and is a principle investigator for the Amphibian Research and Monitoring Initiative for the Ecosystems Mission Area. Her lab has studied boreal toads and other amphibians in the Rocky Mountains for more than 25 years. She is going to be sorcerer for Halloween.

Michael Adams is a supervisory research ecologist at the Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center and is the Lead for the Amphibian Research and Monitoring Initiative for the Ecosystems Mission Area. His lab has studied newts and other amphibians in the Pacific Northwest for the past 25 years. His Halloween plans are a mystery to everyone including himself.

References:

*Bucciarelli, G.M., Clark, M.A., Delaney, K.S. et al. Amphibian responses in the aftermath of extreme climate events. Sci Rep 10, 3409 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-60122-2

**Waddle, J.H., Grear, D.A., Mosher, B.A., Grant, E.H.C., Adams, M.J., Backlin, A.R., Barichivich, W.J., Brand, A.B., Bucciarelli, G.M., Calhoun, D.L. and Chestnut, T., 2020. Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bsal) not detected in an intensive survey of wild North American amphibians. Scientific reports 10(1), p.13012.

***Connelly, P.J., Ross, N., Stringham, O.C. and Eskew, E.A., 2023. United States amphibian imports pose a disease risk to salamanders despite Lacey Act regulations. Communications Earth & Environment, 4(1), p.351.

Papers & Reports Assessing potential collateral damage to tiger salamanders from insecticide applications for plague mitigation

Papers & Reports Genetic Connectivity in the Arizona toad (Anaxyrus microscaphus): implications for conservation of a stream dwelling amphibian in the arid Southwestern U.S.

News & Stories Successful eradication of invasive American bullfrogs leads to co-extirpation of emerging pathogens

Recent ARMI-led research showed the removal of invasive American bullfrogs from livestock ponds and small lakes in southern Arizona also resulted in the apparent local extirpation of two pathogens associated with the bullfrogs. The American bullfrog is native eastern North America but has become widespread in the West, where it preys on many native species of conservation concern. Other recent ARMI-led research from the area suggested that American Bullfrogs could act as reservoirs for pathogens like amphibian chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis; Bd) and ranaviruses, which are often lethal to native amphibians, but less so to American Bullfrogs.

In the early 2000s, American bullfrogs were eradicated from ponds in the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge near the Arizona-Mexico border to assist with the reintroduction efforts for the federally threatened Chiricahua Leopard Frog. In 2015, the bullfrog reinvaded the refuge and was once again removed. This reinvasion from outside the refuge motivated funding for a multi-year, landscape-scale eradication program. In the fall-winter of 2016 and the winter of 2020-2021, the research team tested the water at bullfrog eradication and control (no eradication efforts occurred) sites for the DNA (environmental DNA or eDNA) of invasive bullfrogs, federally threatened Chiricahua Leopard Frogs, and Bd and ranaviruses.

Results from the eDNA sampling showed American Bullfrogs were eradicated successfully from most sites, and where bullfrogs were eradicated, the pathogens were also no longer detected. Chiricahua Leopard Frogs did not increase in occurrence after eradicating bullfrogs, possibly due to an exceptional drought that could have limited the ability of native amphibians to colonize sites.

To our knowledge, this is one of the few studies to link eradication of an invasive species to co-eradication of emerging pathogens. Our spatially replicated experimental approach provides strong evidence that management of invasive species can simultaneously reduce predation and disease risk for imperiled species.

To view the full article click this link: https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12970

Papers & Reports Broad-scale Assessment of Methylmercury in Adult Amphibians

Papers & Reports Successful eradication of invasive American bullfrogs leads to co-extirpation of emerging pathogens

News & Stories 2022 Annual ARMI meeting hosted by the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach, CA

The USGS Amphibian Research and Monitoring initiative met at the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach, CA, during November 1-3, 2022. ARMI researchers and collaborators met in a hybrid meeting to discuss a full suite of topics about amphibian conservation and how to provide the most useful information for managers. Discussions included updates on current regional projects, and the initial wrap up of a 5-year national research effort to look at relationships among disease, contaminants, and demography (e.g., survival). A major topic of the meeting was the identification and development of new efforts to address connections among climate change (current and predicted), and potential changes in range for species broadly distributed across the United States. Such work would include the identification and examination of a suite of landscape-level data such as wetland and pond dynamics, and incorporate other relevant data such as human footprint indices. The modular organization of ARMI makes it uniquely suited to address these and other landscape-scale questions because it facilitates the collection of field data, in a statistically robust manner, and across a broad swath of the country. This capability, paired with the quantitative know-how to effectively use those data, sets ARMI apart. Goals for this project include addressing particular hypotheses about species range and potential drivers of change and developing new continental-scale models that integrate landscape changes, especially in water dynamics. Ultimately, these models can be used to provide better and more easily updated predictions of the presence and persistence of amphibians and other species across the landscape informing management and conservation.