News & Stories

ARMI researchers work on innovative projects throughout the country. News & Stories offer insight into the work of wildlife biologists and the issues facing our nation's amphibians. Explore our site for news & stories about our latest research and how it's used in the management of wildlife and their habitats.

USGS neither sponsors nor endorses non-USGS web sites; per requirement "3.4.1 Prohibition of Commercial Endorsement."

News & Stories USGS ARMI-led conservation program reaches milestone with release of 600 endangered frogs into San Gabriel Mountains

LOS ANGELES, CA – In a remarkable step forward for amphibian conservation, over 600 endangered southern mountain yellow-legged frogs were released into their native habitat in the San Gabriel Mountains earlier this month. The coordinated release — involving 450 tadpoles and 193 subadult frogs — is part of the long-running Southern Mountain Yellow-Legged Frog Recovery Program, led by the U.S. Geological Survey’s Amphibian Research and Monitoring Initiative (ARMI) in partnership with the Los Angeles Zoo, Aquarium of the Pacific, and other agencies.

This program, established in 2006, is one of the most significant amphibian recovery efforts in the country, and the USGS ARMI has played a central role from the outset. As the lead scientific agency, ARMI provides research, monitoring, and strategic oversight for the entire conservation initiative, using decades of expertise in amphibian population science to guide partner efforts and evaluate long-term success.

The recent July 2025 release, carried out at a remote, undisclosed location to protect the animals and their fragile environment, represents a continuation of nearly two decades of strategic reintroductions. Most of the released frogs were bred at the Los Angeles Zoo in a highly controlled, bio-secure facility built specifically for the species. With support from the USGS and partners, the zoo has produced over 6,000 frogs since 2007, all released under carefully monitored conditions to reestablish wild populations.

The species, Rana muscosa, has experienced dramatic population declines in recent decades due to disease, habitat loss, non-native predators, drought, and environmental degradation. Once abundant throughout Southern California’s mountain ranges, these frogs are now classified as Endangered by the IUCN.

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, USGS launched the ARMI initiative in the early 2000s to respond to amphibian declines nationally. The Southern Mountain Yellow-Legged Frog Recovery Program remains a flagship example of ARMI's mission in action. Through intensive monitoring, habitat modeling, and close coordination with state and federal agencies, ARMI ensures that each step in the recovery process — from breeding to release to long-term population tracking — is rooted in scientific evidence.

For more info on the release, please visit the L.A. Zoo's news story: https://lazoo.org/2025/07/l-a-zoo-releases-450-zoo-bred-endangered-frog-tadpoles-into-san-gabriel-mountains/.

News & Stories Amphibian Week 2025 a cross-country success!

Amphibian Week 2025 was celebrated by ARMI scientists who planned and participated in public events from Wisconsin to Florida and from California to Washington, D.C. Over 3000 people participated in these in person events.

On the west coast, amphibian events began early, in February and March, to get folks primed for Amphibian Week. Scientists from USGS Forest and Rangeland Science Center (FRESC, Oregon) partnered with US Fish and Wildlife Service Willamette Valley Refuge Complex to host information tables on two occasions during Winter Wildlife Field Days. ARMI scientists from Western Ecological Science Center (WERC, Point Reyes Field Station) joined FRESC in providing amphibian walks during Amphibian Week. The walk at Point Reyes engaged 4th and 5th graders in not only a walk, but a beta test of an amphibian game. The game was developed by the Einstein Fellows Program with input from ARMI scientists. In southern California (WERC San Diego Field Station) partnered with the Santa Ana Zoo to host a table with activities from coloring sheets to opportunities to practice monitoring for disease by collecting “DNA” on a cotton swab from a plushie “frog”.

In the Rocky Mountains (Fort Collins Science Center), an amphibian-themed art show, “Art Meets Science: The World of Amphibians” was held at a local venue showcasing local art from pottery to watercolors to frog-themed crafts. An evening amphibian walk drew a crowd. At Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center (Missoula Field Station), partners at the Washington Middle School presented a weeklong focus on amphibians with book suggestions and activities that melded biological science and library science.

In the Midwest, scientists from the Upper Midwest Science Center (La Crosse, WI) partnered with The Nature Place to present a talk and an evening amphibian walk. The activity at Myrick Marsh featured field gear like parabolic microphones to listen to frog calls. The National Wildlife Health Center (Madison, WI) partnered with the Kettle Moraine State Forest and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources to host drop-in Amphibian Week activities at the Southern Unit Headquarters in Eagle, WI.

On the east coast, scientists from the Wetlands and Aquatic Research Center (Gainesville, FL) hosted amphibian walks and talks in partnership with the Florida Museum of Natural History. In partnership with the Santa Fe College Teaching Zoo, ARMI scientists hosted an Amphibian Week event with talks, activity tables, and conservation games. The South Atlantic Water Science Center and the New Jersey Water Science Center showed an Amphibian Week informational slide show in the Center lobbies.

In Washington, DC, four ARMI scientists participated in an Amphibian Week kick-off event at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History’s Q?rious exhibit. This event included other federal agencies such as the US Forest Service, with ARMI scientists providing information, activities, games, and displaying live amphibians local to the east coast. ARMI also led an Amphibian Week event at the Smithsonian National Zoo at the historic Reptile House (which also houses amphibians), where scientists partnered with National Zoo staff to provide amphibian demonstrations, pose trivia questions, and provide information about amphibians. Phil the Frog was present at both events, dancing through life and providing inspiration to visitors and staff.

ARMI / USGS also participated in social media focused on Amphibian Week from official USGS posts on Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn and X, to collaborating with partners such as NW Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation in developing posts for the week.

News & Stories ARMI Researchers Team-up on Nationwide Study to Determine How Interactions Between Disease and Mercury Affect Survival of Amphibians

Although it has long been known that stressors such as diseases and contaminants do not act alone, estimating how combinations of different stressors affect amphibians in the wild has generally proven elusive. A new ARMI study helps clarify the threat of the amphibian chytrid fungus (Bd), a pathogen linked with population declines and extirpations of amphibians globally. One of the most surprising results was that Bd reduced adult survival even for some species previously considered resistant to Bd, such as the Eastern Newt. This study also provides the first evidence of that methylmercury can affect survival of wild amphibians, even at sites without obvious sources of mercury contamination. In some cases, Bd and methylmercury appeared to act synergistically to magnify the effect of disease, further reducing survival. This study builds on a recent nation-wide assessment of methylmercury bioaccumulation that used non-lethal sampling, allowing researchers to sample threatened and endangered species that otherwise could not have been included in the study. This new study involved coordinated sampling by ARMI-scientists across the contiguous USA, using a multi-species, multi-population, multi-year modeling effort to provide robust results on the effects of Bd and mercury on adult amphibian survival. The results highlight the challenges associated with managing amphibian populations in the face of endemic disease combined with other environmental stressors.

To view the full article, click this link: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99839-3

News & Stories Dr. Erin Muths Honored with the Alison Haskell Award by Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation

In May 2025, ARMI's own biologist Erin Muths was appointed with the prestigious Allison Haskell Award.

This award honors Erin’s outstanding contributions to amphibian research and outreach, particularly her leadership in conservation research, her role in creating Amphibian Week, and her work with the USGS Amphibian Research and Monitoring Initiative. Her research directly supports science-based decisions for the management, conservation, and recovery of amphibian populations.

Established in the memory of PARC’s first federal agencies coordinator, the Alison Haskell Award recognizes those who exemplify her passion for wildlife and collaborative conservation efforts. Erin Muths is a Research Zoologist at the Fort Collins Science Center who specializes in amphibian demography, disease ecology and conservation. Since joining the USGS in 1995, Erin has made a significant impact in the herpetofaunal research community. Her research projects include reintroductions of boreal toads in the Rocky Mountain National Park, demography of chorus frog and boreal toad populations in Colorado and Wyoming, and salamander disease and occurrence in the desert southwest and Mexico. She is a global leader in amphibian research with an emphasis on the science needs of management agencies.

PARC is a collaborative network established in 1999 to address the alarming declines of amphibians and reptiles. Its mission is to forge proactive partnerships to conserve these species and their habitats, ensuring they are valued and considered in all conservation and land management decisions. PARC brings together a diverse array of members, including individuals from state and federal agencies, conservation organizations, museums, the pet trade industry, nature centers, zoos, the energy industry, universities, herpetological organizations, research laboratories, forest industries, and environmental consultants. This approach makes PARC one of the most comprehensive conservation efforts ever undertaken for amphibians and reptiles.

Congratulations, Erin!

News & Stories Trout, beavers, droughts, and 'precious' frog

The Oregon spotted frog’s scientific name is Rana pretiosa, which translates to “precious frog” in Latin. Precious things are often rare, which is the case with the Oregon spotted frog across parts of its range. It was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 2014. Although several threats are responsible for the Oregon spotted frog’s decline, loss of the wetland habitat it needs to survive is at the top of the list. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s national report on wetlands status and trends reveals nationwide losses. In the Klamath Basin of Oregon and California, it’s estimated that 50-90% of the Oregon spotted frog’s wetland habitat has been lost due to habitat modification and prolonged drought.

U.S. Geological Survey scientists are working with other federal agencies, non-profit organizations, and private landowners to research the effectiveness of restoration projects for multiple species and aid in the recovery of the Oregon spotted frog.

“As landowners working to benefit wildlife, livestock, ecosystem health and water quality, partnering with scientists to research the Oregon spotted frog is a vital piece of our restoration ranching approach,” says Alex Froom, owner of a ranch on the Wood River in Oregon. Restoration work on their ranch includes removing invasive bullfrogs and improving habitat for Oregon spotted frogs.

The non-profit Trout Unlimited, whose work in the Klamath Basin is focused on restoring healthy ecosystems for fisheries, amphibians, and other aquatic species, is a key partner working closely with USGS. Several of the strategies being deployed on federally managed land and private ranches are aimed at improving the drought resilience of aquatic habitats, benefiting a wide range of species.

Historically, the range of the Oregon spotted frog overlapped with that of the North American beaver. Beaver numbers in the Pacific Northwest declined dramatically due to the fur trade in the late 1700s and early 1800’s, as did the ecosystem services they provide. Beaver dams and associated ponds retain water in landscapes that otherwise would not hold it. Warmer water along pond edges promotes development of frog eggs and tadpoles and provides adult frogs with feeding and basking areas. Radio telemetry studies suggest Oregon spotted frogs use other beaver-created features like channels and dams as shelter during the winter. Mimicking these features, or enhancing remnant channels and dams, are possible solutions for improving water retention, increasing shelter opportunities and providing additional habitat.

USGS monitoring of Oregon spotted frog populations is showing early signs of success with these types of projects.

In the longest running study of its kind in the Klamath, USGS researchers counted Oregon spotted frog egg masses and adults along Jack Creek on U.S. Forest Service and private land. Surveys were done at reference sites with no habitat modifications, sites where old beaver ponds were excavated and deepened, and sites that were excavated but had no remnant beaver ponds.

Thirteen years of annual sampling revealed that survival of adult Oregon spotted frogs was almost 20% higher at reaches with excavated remnant beaver ponds compared to reference sites. Satellite images revealed that vegetation at restored sites stayed green later into the summer- an indicator of improved water retention. One promising clue that restoration of this type can work was the fact that frog breeding was concentrated in two excavated beaver ponds relative to other sites.

At a site on Crane Creek, USGS scientists partnered with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Trout Unlimited, and the owner of the Sevenmile Ranch to collect Oregon spotted frogs prior to stream and riparian restoration. Restoration work included redirecting water from a canal back into historical creek meanders and creating a series of ponds. Once restoration was complete, researchers released the frogs and monitored where they went and where they chose to lay eggs. Numbers of egg masses and adults increased in restored areas, indicating modifications to the habitat were favorable for breeding success and survival.

“So far, we’ve seen a noticeable response from Oregon spotted frogs at one site, a smaller but still positive response at another site, and it’s still too early to tell how frogs will respond at two other sites,” says Christopher Pearl, wildlife biologist at the USGS Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center in Corvallis, Oregon. “The signs are encouraging, and we’re also learning a lot about habitat requirements and behavior of Oregon spotted frogs that will help our partners plan future restoration projects.”

That knowledge about how Oregon spotted frogs respond to habitat modifications is directly used for restoration and recovery planning. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is responsible for assessing the recovery of threatened species and reevaluating listing under the Endangered Species Act.

“We’ve been working in partnership with the USGS for over two decades on all aspects of Oregon spotted frog conservation and recovery,” says Jennifer O’Reilly, biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Oregon spotted frog species lead. “USGS has a strong understanding of the Service’s role in implementing the Endangered Species Act and has contributed research that’s crucial to our decision making.”

North American beaver populations are slowly recovering in the Pacific Northwest, and USGS is working with partners to study how Oregon spotted frogs respond to the arrival of beavers and newly constructed dams and ponds. Human-led wetland restoration is generating results now, but beaver may lead the way in the future. Either way, USGS scientists will be there to document the Oregon spotted frog’s recovery.

News & Stories US Forest Service and ARMI in collaboration to bolster the number of endangered Mountain Yellow-legged Frogs in their native range

USGS ARMI biologists have been working with agencies, organizations, and institutions across southern California with the goal of enhancing California’s southern Mountain Yellow-legged Frog populations. Conservation efforts began in the late 1990's when populations were discovered to be significantly declining. Soon after, the frogs were listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). ARMI biologists helped develop a captive breeding and headstarting program for the purpose of rearing and raising offspring to release back into the wild. Local zoos, including the Los Angeles Zoo and Botanical Gardens, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, Santa Ana Zoo, Omaha's Henry Doorly Zoo, and The Aquarium of the Pacific were eager to help.

This past summer, USGS led a multi-partner group that trekked into the San Gabriel Mountains carrying backpacks full of young frogs to release into their native habitat. Please check out the following miniseries for the full coverage of this endeavor.

US Forest Service - Episode 52: For the Frogs - Reintroduction

Transcript - Download directly (6MB)

News & Stories ARMI scientists are delegates to the World Congress of Herpetology

The 10th World Congress of Herpetology was held in the city of Kuching, in Sarawak, Malaysia (northwest Borneo) August 5 – 9. ARMI scientists Brian Halstead, Blake Hossack, Pat Kleeman, and Erin Muths presented research papers. There were over 1400 delegates at the Congress, with > 900 contributed talks and 33 symposia.

Halstead and Muths organized a symposium targeted at graduate students (What Editors Want: A Guide to the Publication Process for Graduate Students) that included talks from 7 past and present editors, including Judit Voros, co-editor of Amphibia-Reptilia and Secretary General of the World Congress.

Hossack presented a talk co-authored by ARMI scientists Kelly Smalling and Brian Tornabene titled: “Energy-related secondary salinization of wetlands: Coordinated experiments and field surveys to identify mechanistic links with amphibian abundance”. This invited talk was included in the symposium titled: Haunting the seaside: Integrative biology of salt tolerance in amphibians.

Halstead presented a talk titled: “Effects of translocation and head-starting on giant gartersnake (Thamnophis gigas) behavior and survival”, co-authored by USGS scientist A. M. Nguyen and B. D. Todd (University of California, Davis). This invited talk was included in the symposium titled: Improving conservation and mitigation outcomes of snake translocations—global lessons.

Kleeman presented a contributed talk co-authored by Halstead and J.P. Rose (ARMI scientists), and collaborators from the Nevada Department of Wildlife, K. Guadalupe and M. West, titled: Initial demographic estimates for two species of narrowly endemic toads in central Nevada: Anaxyrus monfontanus and Anaxyrus nevadensis.

Muths’ presentation, co-authored by L. Bailey, A. Fueka, L. Roberts (Colorado State University) and B. Hardy (Chapman College), was in the symposium titled: Improving animal welfare. This invited talk was titled, “Methods in marking toads: PIT tagging versus photography”.

The World Congress is held every four years on different continents with the specific aim of facilitating attendance from herpetologists around the world especially those from developing countries. The first World Congress was held in Canterbury, Great Britain in 1989, with subsequent congresses in locations including China, Brazil, Australia, and Canada. ARMI hosted a symposium on amphibian decline in 2012 at the 7th World Congress in Vancouver.

Congress delegates in Kuching enjoyed multiple plenary talks with topics ranging from Bornean flora and fauna, to the Biogeography and Evolution of reptiles in the Arabian Peninsula, to Frog diversification in Old World tree frogs.

News & Stories Effects of Harmful Algal Blooms on Amphibians and Reptiles are Under-Reported and Under-Represented

USGS ARMI scientists recently published a critical review on what is known about the effects of harmful algal blooms (HABs) on amphibians and reptiles.

HABs are a persistent and increasing problem globally in both freshwater and marine environments, yet we still have limited knowledge about how they affect wildlife. HABs can occur when colonies of algae have abundant resources, grow rapidly, and produce cyanotoxins. This natural phenomenon was first described in the late 1800s but have become more common due to increases in nutrient inputs and availability (e.g., from agriculture or runoff) and global temperatures that favor their growth.

Although semi-aquatic and aquatic amphibians and reptiles have experienced large declines and occupy environments where HABs are increasingly problematic, their vulnerability to HABs remains unclear. The current review was designed to synthesize existing information of the effects of cyanotoxins on amphibians and freshwater reptiles. The information gained by evaluating and synthesizing previous studies and reported mortality events could enhance monitoring and conservation efforts while also guiding future studies on both amphibians and reptiles.

Our review highlights how cyanotoxins can be lethal and negatively affect larval amphibians, but information on effects on reptiles or embryonic and adult amphibians is lacking, apart from a few observational studies. Cyanotoxins can have systemic effects and negatively influence reproductive, digestive, and liver function in amphibians. Given that amphibian and some reptile populations are declining worldwide, it is important to increase monitoring and experimental efforts to understand the singular and synergistic effects of these toxins. It will also be important to better understand the events that cause algal blooms to synthesize and release toxins and effects of HABs that do not produce cyanotoxins. We also propose future near-term and long-term studies that could help clarify the population-level effects of HABs on amphibians and reptiles and could enhance monitoring and management efforts, especially in areas where HABs have been documented consistently.

News & Stories Fish & Wildlife Service 2023 Recovery Champions

California red-legged frog recovery partners have collectively moved the species closer to recovery, most notably through their efforts to reestablish the frog in the southern-most portion of its range where it had disappeared decades earlier. Over the years, these individuals have demonstrated extraordinary vision, leadership, and collaboration in developing a bi-national plan for reintroducing the species, which includes transporting egg masses from Baja California, Mexico, to sites in Riverside and San Diego counties, California. Efforts to work with landowners to identify suitable habitat for releases, along with management and monitoring of the species, exemplify the Service’s mission of working with others to conserve species and their habitats for the benefit of the American people.

Fish & Wildlife Service has recognized ARMI biologists Robert Fisher, Adam Backlin, and Elizabeth Gallegos as crucial partners for the success of this project.

News & Stories Climate change and Cascades Frog

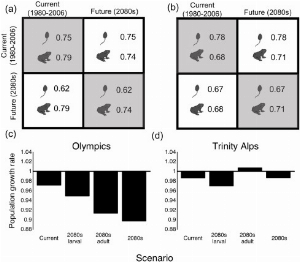

A new paper by Kissel et al shows how complex life cycles interacting with climate change can lead to counter-intuitive outcomes for amphibian populations: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecochg.2023.100081